Reflections on the 2025 Falling Walls Science Summit

December 9, 2025

By Emily Howell, Research and Impact Fellow, Rita Allen Foundation

At the Falling Walls Science Summit in Berlin, Germany on November 9, I joined Civic Science Fellows Christine Custis (CSF 2024-25), Alicia Johnson (CSF 2024-25), and Erica Palma Kimmerling (CSF 2020-21), as well as funding partner Brooke Smith from The Kavli Foundation. Marking the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Falling Walls Science Summit each year asks, “Which are the next walls to fall?”

The Fellows co-led conversations with scientists on societal implications of their research breakthroughs. The discussions were an experiment to see how we could seed civic science approaches in thinking on science and technology innovation, which felt particularly meaningful against the backdrop of such a pivotal moment in history.

If you’ve been to Berlin, you’ve probably seen the line indicating where the Wall zagged around and through buildings across the city, dividing the communist sector in the east from democratic sectors of the west during most of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall seemed to appear suddenly in East Berlin, with soldiers putting up barriers overnight in August 1961, and seemed to “fall” suddenly 28 years later, over the course of a press conference with East German leaders on November 9, 1989.

I was already somewhat obsessed with Berlin’s history, but seeing the city through the lens of the Civic Science Fellows program brought up new connections to ponder, particularly around large-scale change and innovation. In the Fellows program, we’re exploring how to better recognize systems change in its early stages: What precipitates changes in cultures, policies, institutions, and norms? Such change can seem to happen “gradually and then suddenly.” The suddenly, if it occurs, isn’t always so obvious as dismantling a concrete wall, but it can often seem like magic or epiphany, whether fluke or fate. The gradually, though, is usually the power we don’t see.

Berlin is full of stories, often still hidden, of what gradually led to the fall of the Wall, and to the current moment. This city is also one of those places where different approaches, norms, and systems collide, illuminating each other and often creating something new. The Falling Walls Summit leans into this setting.

The organizers designed the event to bring together people who work in different sectors, disciplines, and countries, to share and debate what’s next in science. Conversations on panels and round tables over three days focus on metaphorical walls falling thanks to scientific breakthroughs, and thanks to the relationships across public and private sectors that enable such breakthroughs and their transfer to societal applications. Events included discussions between CEOs from philanthropies like the Volkswagen Foundation and companies like Siemens; directors of government research centers such as Los Alamos National Laboratory; heads of universities; and government leaders, including the State Secretary of the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology, and Space.

Core to the Summit are the “Breakthroughs,” which are awards to researchers for “innovative and impactful research redefining scientific frontiers” in life sciences, physical sciences, engineering and technology, social sciences and humanities, or art and science. Less discussed, though, were the societal implications of such breakthroughs. Most conversations didn’t move beyond possible benefits from new innovations into the many implications, tensions, and trade-offs that any area of research or change brings to its surroundings. What are the relevant democratic, human, and civic factors tied to an innovation? What role do broader publics, within and beyond the roles of industry, government, and universities, play in determining innovation? And what walls are next to fall—suddenly or gradually, planned demolitions or not, destructive and generative—in these domains?

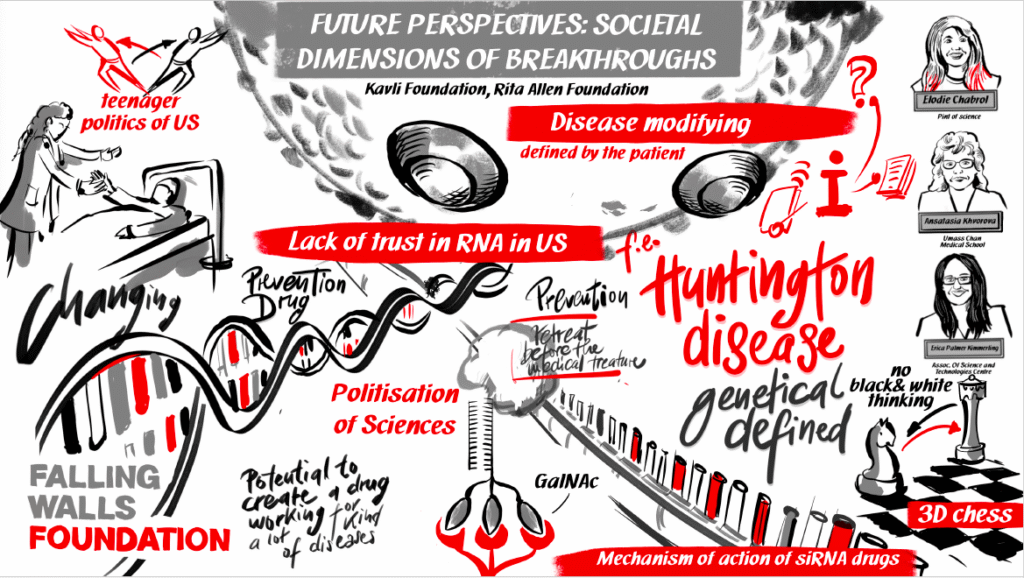

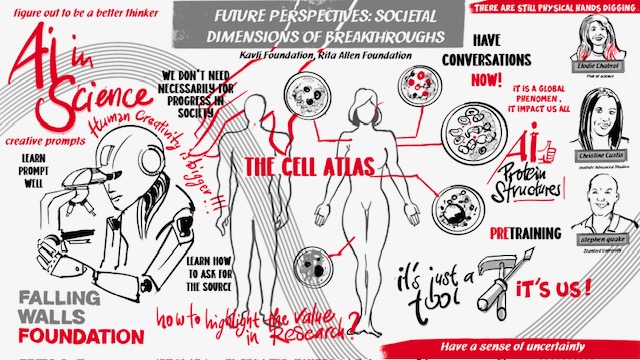

The Civic Science Fellows each led a conversation that ventured more into these questions during “Insight Cafés” that brought together each Fellow with one of the Falling Walls Breakthrough researchers of the year to discuss with audience members the possible implications of the groundbreaking research. Attendees perched on sofas and stools in a glass-walled room next to the coffee station, and a large screen showed an illustrator live-sketching the conversation. The Fellows and scientists fielded a wide range of questions, such as whether RNA-based therapies could also be preventative, how we define “life” (and who gets to define it), and the implications of (often unknown) biases in AI training sets and human health research samples.

Erica Kimmerling opened with an Insight Café discussing RNA-based therapies with Anastasia Khvorova, a molecular medicine researcher at the UMass Chan Medical School, who is developing RNA-based drugs that regulate gene expression, particularly for neurodegenerative diseases like Huntington’s. In response to a question about whether RNA-based treatments could also be preventative, Kimmerling described how prevention requires a shift in how people engage with a technology, in response to changes in who is impacted, and perceived costs and benefits. Khvorova talked about the higher regulatory bar that preventative treatments (given to healthy people) must pass in clinical trials. They also discussed how people’s health choices are personal and complex, but also relevant for engagement: Khvorova described how therapies with clear benefits and low side effects, such as statins’ use to lower cholesterol, are widely accepted, and Kimmerling shared how even in the seemingly clear-cut case of statins, a family member decided to stop taking them because of side effects.

In the second Insight Café, Alicia Johnson discussed the societal implications of research into the origins of life with John Sutherland, a molecular biologist at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the United Kingdom, who has revolutionized the study of life’s origin by understanding the basic building blocks required and how to derive those from a single starting material. In response to an audience question about how we define what “life” is and who gets to define it, Sutherland said he defines life on a spectrum in his research, but that it’s something no one definitively knows and scientists disagree on. He shared how academic systems should be designed around questions, rather than disciplines, to better explore this and other areas. Johnson described how “wild speculation” exercises with scientists to imagine different implications of their work, even in early stages before applications are clear, can be useful.

In the third gathering, Christine Custis discussed AI in human biology research on the Human Cell Atlas project with Stephen Quake, an applied physicist at Stanford University who leads the global effort to map all cell types in humans. In responding to a question about biases in AI training data, Quake described how training sets are usually proprietary black boxes, and Custis talked about the value of many diverse, more-specified models, rather than universal generalized models. Custis also described the many physical impacts of AI, how it doesn’t exist purely in the digital world but also depends on mines, data centers, and human trainers, with impacts on and from each. Quake added that these and other costs, and even the basic economics of AI, are largely hidden from users. When an audience member asked if current systems reinforce the separation between people who do research and people who think about its implications, with losses for both, Custis mentioned the Civic Science Fellows program as one example of how to support boundary-spanning, and that people on both sides should recognize they don’t need permission to incorporate bridging as part of their work.

The Insight Cafés felt like successful experiments on several levels. Audiences were engaged and had more questions and follow-ups than could fit in the time. The participating scientists said they enjoyed the opportunity to think about their work in new ways. Two shared that they rarely had the chance to think about broader implications of their research.

But the conversations were also encouraging because of how they illustrated a current running through the sessions that hadn’t been acknowledged until Custis succinctly said at the end of her session, “Science is plural.” Discussions about science and civic life often fail to acknowledge the fact that what “science” means differs across contexts and people, even though this difference is where generative tension and meeting of ideas seems to be. Over the course of each discussion, such plurality and its implications became more tangible. People with different perspectives found that they disagreed, but also agreed, often in ways they didn’t recognize before. Through each conversation they used questions and discussion to expose concepts typically either taken for granted or hidden in one set of norms and practices.

Both Falling Walls and the Civic Science Fellows program experiment in how to connect those pluralities across the walls that separate them. The goal is to see what innovation in science and civic life emerges when those walls come down, even if it happens gradually. What emerged from the discussions in the Insight Cafés felt like the innovative fodder for science and civic life.

Read more about work from Fellows with ideas connected to Berlin, Eastern Europe, history, and “falling walls”:

- Theresa A. Donofrio (CSF 2024-25) has a background in memory and museum studies, which she now translates into her work with ASTC’s Seeding Action initiative focused on generating active hope on planetary health.

- Tim Maximilian Sels (CSF 2024-25) is from Berlin and has expertise in organizational behavior. For his fellowship, he partnered with the Data Innovation Lab to study media’s roles in public diffusion of science.

- Ovidia Stanoi (CSF 2024-25) grew up in Romania after the fall of the Communist government and became interested in how cultures, communication, perceptions, and trust interact, particularly in how people regulate what they say and do. She now applies that to facilitating climate communication.